(*Full Disclosure: They’re Fictional)

(*Full Disclosure: They’re Fictional)

John Galt (First of Twelve)

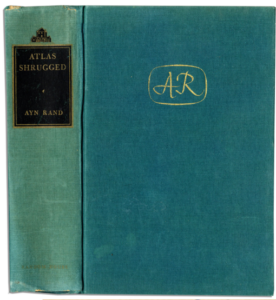

At age seventeen when my world was young and soft like clay, I spied a book in the high school library—my only place of enlightenment in that damned institution of “education”—whose cover and title grabbed my attention. It was faded and frayed from age not use. The viridian green cover had the letters A and R beautifully stylized on the front in gold foil letters. The archaic binding was interwoven fabric with crosshatched threading. You could scratch your fingernails across it and the uneven surface felt good.

It smelled good. A faint aroma of vanilla and almond (I learned much later in life this “old book smell” is caused by the breakdown of chemical compounds in the paper) subliminally stoked my hunger to devour this book.

It was big and heavy. Substantial. Eleven hundred and sixty-eight pages. The title on the cover page was Atlas Shrugged, and it was written by someone I had never heard of with the unpronounceable first name of Ayn. Only much later in life did I find out the name rhymed with the word mine and to my surprise discovered that Ayn Rand was female. I’ve also found it is a book that many people say they have read—but few really have.

I opened the thick and uneven yellowed pages and the questioning first sentence seared my imagination. Who is John Galt?

I determined at that moment to discover the answer for myself. I had to know. I feverishly read that book in two days and immediately turned back to page one and read it again.

It was an education for this very naive seventeen-year-old. A cataclysmic event that did violence to my innocence. In the most orgasmic of ways (it occurs to me as I write these words thankfully it was the first of many). It remains the single most influential book of my life and the context and timing were pivotal.

I have read it four times now, the last reading was only three years ago. It has the same affect every time. No other novel (with the possible exception of The Magus) comes close.

The question invoking Galt’s name lends a mystical quality to the character of the protagonist, almost as if he were a mythological being. The author likens him to a modern day Prometheus. A man able to carry the earth on his shoulders. A hero of epic proportions, an ideal person. He is a leader of vast intellectual gifts and unswerving rationality.

What makes John Galt so unique is the way he uses his mind—with an unflinching commitment to facts, even if they are unpleasant, painful, or frightening. His rationality embodies the novel’s essential theme: Only by means of the mind can human beings achieve prosperity on earth.

I consider the mind one of the four essential aspects of my being. And as a seven (the Epicure) on the Enneagram Personality Test, my personality is located in the “thinking” center. But this is not why John Galt influenced my life in such a profound manner.

I have pondered Rand’s philosophy of objectivism and the value of logic and reason versus cognitive emotional theory for years. And I have serious issues with objectivism and cannot agree wholeheartedly with the essential theme of the book.

But the ideal of John Galt permeated my being. Long before the creation and influence of the iconic 1997 commercial narrated by Steve Jobs, Galt personified and foreshadowed these words (these ideals) to me:

Here’s to the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the square pegs in the round holes…the ones who see things differently— they’re not fond of rules…You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them, but the only thing you can’t do is ignore them because they change things…they push the human race forward, and while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius, because the ones who are crazy enough to think that they can change the world, are the ones who do.

Let’s briefly consider three of those ideals.

First, the ideal of innovation. The context and the timing of my initial reading of Atlas Shrugged were pivotal. At age seventeen, I barely knew the existence of the word innovation, but the ideal had already began to permeate the wallpaper of my life. My adolescence marked the beginning of a torrid love affair with science fiction books.

Isolated in the Appalachians and with no television to distract me, I gobbled up tattered paperbacks by Isaac Asimov, Aldous Huxley, William Gibson, Mary Shelley, George Orwell, Robert A. Heinlein, Ursula K. Le Guin, to name only a few.

The genre became my ticket to new and exciting ideas—ones I couldn’t imagine even in my wildest dreams. They were portals to revolutionary technology and unimaginable possibilities. Science fiction provided a frightening yet captivating literary escape. It gave me the courage to glimpse into the future and it exposed and debunked some of my greatest misconceptions of the past and present.

John Galt was a fearless iconoclast forging forward-thinking technology. Three innovations from Atlas Shrugged championed by Galt forever captured my imagination. The utopian retreat called Galt’s Gulch, the motor powered by static electricity and Reardon metal—all with the potential to change the world forever.

The journey of this fictional hero taught me the value of clarity, disruptive innovation, and without a doubt, fanned the flame of a full-hearted embrace of technology.

Second, the ideal of self-reliance. Many think this quote is John Galt at his finest: “I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson seems to agree:

There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the wide universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given to him to till.

This ideal of self-reliance was hard for me. I let the institutions of life deceive me. I was taught I could rely on my family, my church, my education, my government, and my god. But in the time of my deepest and darkest suffering they were not reliable. They were not there. None of them.

The church lies were especially damaging. I was taught I could not trust myself. That my heart was deceitful. That only God knows the heart.

Lies.

I wasn’t able to think for myself, much less trust myself.

But deep suffering and isolation has a way of leading to the painful truth of self-reliance if we are willing to endure the struggle and have the courage to face it. It teaches that I must not be concerned with what other people think, because there will always be those (family, church, education, government, the gods we’ve been taught to fear) who think they know our life purpose better than we know it.

Galt believes that people must pursue their own self-interest—that the requirements of a person’s existence require that they seek their own purpose. Galt repudiates any form of self-sacrifice or the renunciation of one’s values. As I’ve grown older and able to think for myself, I’ve often said we’ve sacrificed our souls at the altar of self-denial.

In Galt’s philosophy, living by sacrificing one’s values is impossible; life requires attaining those values. The code of self-sacrifice—whether the sacrifice is to God, society, or something else—is a death sentence. People who try to live by self-sacrifice end up destroying themselves.

The words of Emerson reverberate through time: “Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.”

Third, the ideal of freedom. There is no other more important word to me (with the possible exception of love) than freedom.

In his pivotal speech, John Galt states that man needs freedom to apply his intellect to pursuing the values that his life requires. Galt is opposed to socialism, fascism, communism, or any other type of system that tyrannizes the mind of man. I would add American education, materialism, government, and religion as systems to oppose—institutions that value control over freedom.

The essence of Galt’s philosophy is that the mind is the source of human well-being, and the mind must be free. I posit not only the mind, but also the soul, spirit, and body as primary components of a cohesive human being and that they all must be free.

Perhaps this ideal is why those like me are considered the crazy ones, misfits, rebels, troublemakers, square pegs in round holes, ones who see things differently. And it’s most definitely why we’re not fond of rules, why we challenge authority, why we oppose government interference, and why we defy control.

It’s why (much to the dismay of many of my religious friends) I gave my book Sex, Lies & Religion the subtitle: Enjoying The Freedom of Unconditional Sexuality.

I’ve recently encountered the existential philosophy of John-Paul Sartre. His writings have gripped me like few others. I heard his name countless times but had never seriously studied his life and beliefs. As I read more and more about him—I found in him a soulmate. I understood why his lover Simone Beauvoir was forever captivated and inspired by him. Many feel his life and philosophy can be summed up in one word—freedom.

Listen to his words: “Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.”

And more: “Freedom is what you do with what’s been done to you.”

I am free. Free at last.

At age seventeen, these words by Ayn Rand were seared indelibly into my being. They are branded even deeper today:

Do not let your fire go out, spark by irreplaceable spark in the hopeless swamps of the not-quite, the not-yet, and the not-at-all. Do not let the hero in your soul perish in lonely frustration for the life you deserve and have never been able to reach. The world you desire can be won. It exists..it is real..it is possible..it’s yours.

So Who is John Galt? That’s a question I believe each of us are free to answer by blazing the path of our own unique way.

One response to “My Heroes Have Always Been Fake*”

Very thought provoking, as always, Randy. I find myself touched to the core; agreeing with nearly all of your conclusions. I’ve always loved the Steve Jobs quote. It gives hope to those of us who have never “fit in”, and are still trying to find our way.