They call me a backslider. To this day.

My mother said she didn’t know how she birthed me. My former pastor said I’d abandoned the faith. My tribe said I was sliding away from God—backward, downward, into perdition, that I had gone off the deep end.

For almost twenty years, I’ve carried those words in my heart. Backslider. It meant traitor. It meant “lost”. It meant I’d become an outsider in the only world I’d ever known.

But here’s what I’m learning: a backslider is someone whose beliefs diverge from established doctrine—someone the intellectual world calls heterodox. Two different words for the same trajectory, viewed from different vantage points. One is visceral, the other intellectual.

But both are about the same essential truth: I could no longer stomach the orthodoxy I once served with sincere devotion.

The Weight of Appalachian Shame

In my Appalachian religious culture, “backslider” carried particular weight that’s hard to convey to those who didn’t grow up in that insular world. Mountain evangelicalism was authoritarian, fundamentalist, and deeply suspicious of independent thinking. The threat of being labeled a backslider functioned as social control in communities where church and family were essentially synonymous.

To backslide wasn’t just to lapse in faith—it was to betray your tribe, abandon your family, reject your identity. It was to become an outsider in the only world you’d ever known. When my mother told me she didn’t know how she birthed me, she was articulating what the whole community felt: I had somehow slid away from who I was supposed to be.

The term “backslider” emerged in the 1550s-1580s during the Protestant Reformation, combining “back” with “slide” to create imagery of someone slipping down a slope toward perdition. It appeared in the 1611 King James Bible and was weaponized during America’s Great Awakenings to maintain control over converts. The doctrine of backsliding created perpetual anxiety—you could never be certain you were truly saved because the possibility of falling away always loomed.

This manufactured insecurity was the point. It motivated “exacting spiritual self-discipline,” kept people obedient, attending church, tithing, conforming. And in Appalachian communities where everyone knew everyone’s business, where shame was currency and reputation was everything, being labeled a backslider was social death.

The Intellectual Awakening

But here’s what they never anticipated: some of us were voracious readers. Some of us couldn’t stop asking questions even when the answers threatened to unravel everything.

If you’re reading this and recognizing yourself—if you’re the person who keeps reading the forbidden books, keeps asking the dangerous questions, keeps feeling like something’s wrong with the answers you’re getting—you’re not alone. The intellectual awakening feels like betrayal because it is betrayal. You’re betraying the system that trained you not to think.

The heterodoxy began long before I left—it started with taboo writings, with uncensored history, with philosophy professors at my fundamentalist college who inadvertently introduced me to dangerous ideas.

Montaigne. Sartre. Jung. Existentialist philosophy. The bloody, murderous pattern of Christianity across centuries. The uncomfortable truth is that orthodox beliefs about sexuality, the body, and human nature didn’t align with lived reality. Every book was preparation, every question was my mind staging a quiet revolution.

Heterodoxy is the intellectual equivalent of backsliding. While my Appalachian tribe saw me sliding away from faith, what was actually happening was far more threatening: I was thinking my way out of indoctrination. I spent thirty years in Southern Baptist pulpits believing every word I said, every song I led. I served with honor under men who demanded unthinking obedience, who taught that questioning God was sin, who insisted the Bible was infallible, and any deviation meant the whole edifice would collapse.

The questions multiplied. If the body is so sinful, why did Athanasius say God chose to meet us in our sensuality? If doubt is sin, why does faith require courage to question? If medieval doctrines don’t align with real life in the modern world, whose failure is that—mine or theirs?

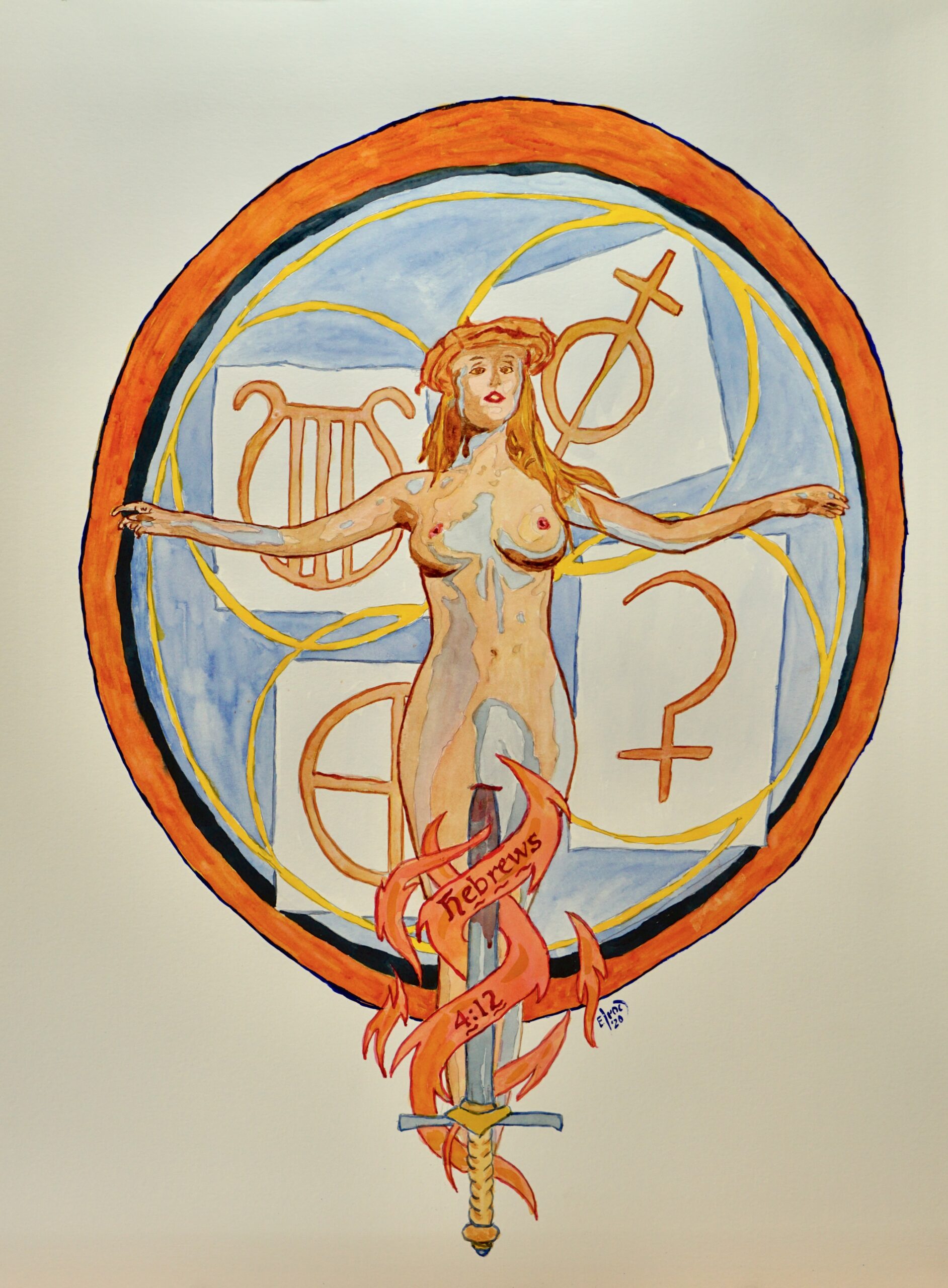

The Four Essentials: A New Framework

Eventually, I needed language for what I was moving toward, not just what I was leaving. I needed a framework that integrated everything evangelical Christianity had fragmented in me. My heterodoxy formed around what I now call the Four Essentials: Body/Sensuality, Mind/Curiosity, Soul/Intimacy, Spirit/Freedom. Orthodox and evangelical Christianity demand you privilege Spirit while suppressing Body, Mind while submitting to Authority, Soul while conforming to Community. I discovered—painfully, expensively—that wholeness requires integration, not fragmentation.

This is what makes both “backslider” and “heterodox” such apt descriptions. I slid backward from their moral mythology into the freedom of authentic living. And I diverged from their established doctrine because intellectual honesty required it. The evangelical world needed “backslider” as a linguistic weapon to shame those who dared to think for themselves. But I’ve turned it into a rallying cry for those sliding backward into freedom, authenticity, and integrated wholeness—away from the fragmentation that evangelical moralism demands.

Reclaiming the Language

That’s the real power of understanding etymology: once you see how language has been weaponized against you, you can seize it and make it your own.

Yes, I’m a backslider. The evangelicals call me that, and some even call us “exvangelicals”—those courageous ones who believe deeply that our work will restore and reform rather than destroy and condemn. We backsliders have ideas in sync with the needs of our times. We’ve broken the chains of institutional life, challenged the white evangelical male collective, and refused to let fear of condemnation silence our questions.

And yes, I’m heterodox—magnificently, defiantly, gloriously heterodox. My beliefs diverge from established doctrine because that doctrine required me to amputate essential parts of myself. I’m a Renaissance Redneck who reads existentialist philosophy and paints watercolors in Barcelona. I write openly about sexuality and shame, about the sacred nature of the body, about psychedelics and consciousness. Topics that would scandalize my former congregation have become the foundation of authentic living.

The Cost and the Freedom

Make no mistake—this cost me everything. My tribe, most of my family, my “closest” friends, my home, my heavenly father. It devastated me financially, psychologically, emotionally, spiritually. To this day I suffer symptoms of post-traumatic stress from religious trauma.

But the peace that permeates my being since leaving religion? I cannot describe it to you. The integration I feel in body, mind, soul, and spirit? The freedom to ask questions without fear, to live without shame, to embrace my sensitivity as gift rather than flaw? This is worth every loss.

The orthodox world will call you heretic, reprobate, traitor, backslider. They must. Your very existence threatens their carefully constructed walls. But here’s what they won’t tell you: life outside those walls offers radical hope, joyous destiny, and the possibility of becoming who you really are.

I am backslider. Heterodox. Renaissance Redneck. Herald. Complicated, multi-layered, ever misunderstood. And finally, gloriously free.

The question isn’t whether you’ll be labeled. The question is whether you have the stubborn courage to reclaim the language they use against you and make it your own battle cry for liberation.

So yes, call me a backslider. I slid backward from moral mythology into the freedom of authentic living.

Call me heterodox. My beliefs diverge from established doctrine because that doctrine required me to amputate essential parts of myself.

I’m both. And I’m finally free.

Maybe you are too. Or will be.

Leave a Reply