From: A Life in Four Movements (An Unfinished Symphony)

My father is dying at home in hospice care.

I’ve been calling my mother more—once a week now instead of once a month—and every time she answers, her voice startles me. Not because it’s aged (though it has), but because it carries centuries of the Cumberland Plateau in its vowels. She still says “authuritis” and “addvul” and “coopons.” She still asks, “Lawd willin’,” at the end of every conversation. She wants to know if we have TV and pineapple in Spain.

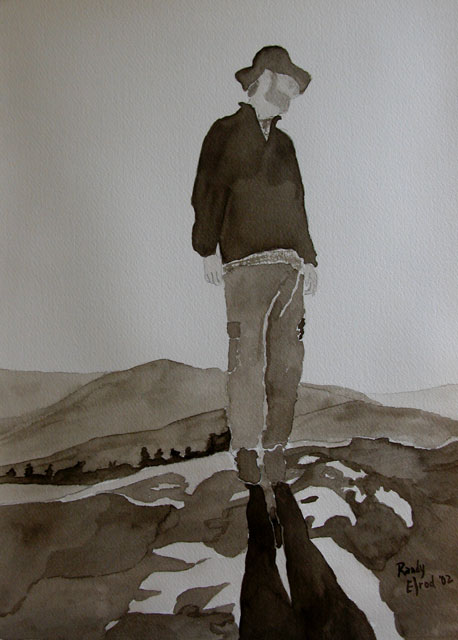

I have ancient cassette tapes from a conference when I was 21. I cringe when I hear myself—that pronounced drawl thick as molasses, words tumbling out lazy and slow. My family still talks that way. Time and workplace peers have softened it some, their kids even more. But they’re southern through and through, all living within a mile of each other in the foothills of Appalachia, the way the Elrods have always done.

And then there’s me. The one who left.

I read an essay recently about the death of the southern drawl. Linguists say it peaked with Baby Boomers—my father’s generation—and has been declining ever since. Migration patterns, suburbanization, the internet. Kids playing video games with peers from across the country, adopting what one father called a “YouTube accent.” The Southern Vowel Shift, they call it, and it’s shifting right out of existence.

When I made the outrageous decision to move away from the Elrod clan to Stuart, Florida—just north of Palm Beach—they couldn’t believe it. Have never forgiven me, really. My new church was filled with transplants from New York and New Jersey who ruthlessly mocked my accent. Every Sunday I’d stand before them, and every Sunday they’d snicker at the redneck who wandered in from Dogpatch.

My salvation was that when I sang, the accent disappeared—like Gomer Pyle on that vintage TV show. My rich baritone got me through a multitude of sins. And when my vocal coach from Juilliard insisted on working with my speaking voice (he dreamed of me singing oratorio in New York), I learned to lift my soft palate, to enunciate, to pass.

The first Christmas I came home, everyone stared at me like I’d grown a second head. “Randy, why are you’ns talkin’ so weird? You thank you’uns is something now that you livin’ down in that fancy pants place?”

I couldn’t win. Ridiculed in Palm Beach for talking like a redneck. Ridiculed at home for having “airs.”

My children grew up with northeastern accents. They were never accepted into the fold. Still aren’t. They don’t visit my family. My family “shore” hasn’t visited them—not once in 50 years. My grandchildren (whom I’ve never met) have a father from Australia. Their mother, my daughter, has a northeastern accent. Those kids will never know the southern drawl of the Elrod family. My two daughters, raised in Palm Beach and Franklin, Tennessee—two of the most affluent places on earth—refuse to believe I grew up in poverty in Appalachia. They’re ashamed of it.

The linguist Amy Clark says, “I carry my history in my mouth. My words and my grammar patterns are full of centuries of history. My ancestors are with me every time I speak.”

But what happens when the mouth changes? When it learns to code-switch, to pass, to survive? When your children speak a different language entirely, and their children don’t speak to you at all?

There’s a line in the essay about people who lose their accents walking a “linguistic tightrope”—made fun of at school, made fun of at home. “You’ve gotten above your raising,” they say. “You’re too good for us now.”

Fifty years later, I’m still walking that tightrope. Still the Renaissance Redneck who belongs everywhere and nowhere. Here in Barcelona, learning Spanish, I discover that even though I killed the drawl decades ago, the slowness remains—that lazy, deliberate pacing of words is baked into my bones. It’s antithetical to Spanish, which tumbles out rapid-fire, all staccato urgency.

Crazy that the ghost of what I tried to erase is still sabotaging me. My father lies dying, his words still molasses-thick, still speaking in tongues I had to unlearn to survive. My mother asks if we have pineapple in Spain.

And somewhere on the other side of the world, grandchildren I’ll never meet are growing up speaking English with Australian inflections, completely untethered from the mountains that made me, the poverty that shaped me, the accent I had to kill to become whoever the hell I am now.

Thomas Wolfe was right. You can’t go home again. But apparently, you can’t take it with you either.

Lawd willin’.

Leave a Reply