These profound words written by Audra Lorde—”For once we begin to feel deeply all the aspects of our lives, we begin to demand from ourselves and from our life-pursuits that they feel in accordance with that joy which we know ourselves to be capable of”—speak to something I lived for decades without understanding.

The erotic isn’t just about sex, though it certainly includes that. It’s about feeling deeply, about refusing to settle for the numbed-out existence that institutions demand. When you truly awaken to erotic consciousness, you can no longer tolerate shallow relationships, meaningless work, borrowed beliefs, or any aspect of life that doesn’t resonate with your deepest capacity for joy.

This is precisely why evangelical Christianity fears it. The erotic knowledge that “empowers us, becomes a lens through which we scrutinize all aspects of our existence” is dangerous to systems of control. When you start demanding that your spiritual life feel as alive as your sexual life, when you insist that your work be as passionate as your most intimate moments, when you refuse to separate body from soul—well, that’s the end of institutional compliance.

The Grave Responsibility of Aliveness

Lorde’s phrase about “grave responsibility…not to settle for the convenient, the shoddy, the conventionally expected, nor the merely safe” reads like a manifesto for the second half of life. At 67, I finally understand that living erotically—fully alive to sensation, beauty, connection, desire—isn’t self-indulgence. It’s spiritual responsibility.

For three decades, I stood in Southern Baptist pulpits espousing a gospel that demanded I sever mind from body, spirit from flesh, sacred from sensual. The result wasn’t holiness—it was fragmentation, the slow death of authentic being in service to borrowed righteousness.

The Art of Awakening

My own erotic education didn’t come from church-approved sources. It came from artists brave enough to explore the full spectrum of human experience: the raw honesty of Henry Miller, the psychological complexity of John Fowles’ The Magus, the unapologetic sensuality of Anaïs Nin’s diaries.

Films like Emmanuelle (1974) and Lady Chatterley’s Lover weren’t just entertainment—they were invitations to consider what life might look like if we stopped apologizing for our humanity. Even the campy Camp Wannahumpa series offered permission to laugh about desire instead of hiding from it.

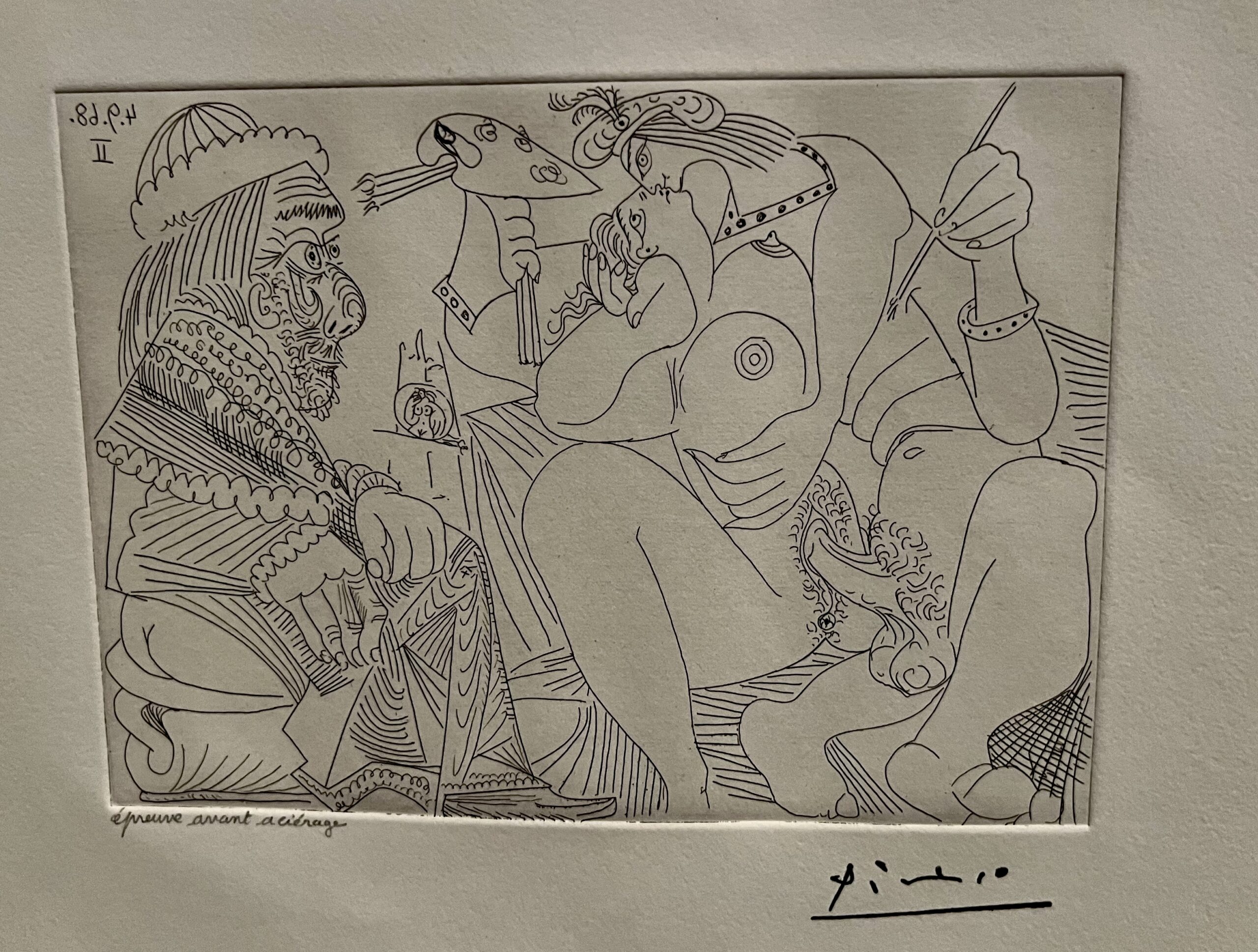

The photography of Robert Mapplethorpe, with its stark beauty and uncompromising gaze, taught me that the erotic could be both tender and powerful. Picasso’s late graphite drawings—created in his eighties when most men are supposedly “past all that”—showed me that erotic energy doesn’t diminish with age; it deepens, becomes more essential, more honest. (See one of them at beginning of this post.)

The Barcelona Difference

Living in Spain has been a revelation about what culture looks like when it doesn’t war against the erotic. Here, sensuality isn’t the enemy of spirituality—it’s part of the same conversation. The same culture that created magnificent cathedrals also celebrates nude beaches, tantric massage, fine wine, passionate conversation, and the full spectrum of human desire without shame.

From my Spanish perspective, American evangelical culture’s fear of the erotic looks increasingly bizarre.

We create a society where violence is acceptable entertainment but sexuality requires content warnings. Where we can politics in Sunday School but not the Song of Solomon. Where we produce men so disconnected from their own desire that they become dangerous to themselves and others.

The Integration of Age and Desire

At 67, I’m discovering that erotic consciousness becomes more important, not less. When you realize how limited your time is, you stop tolerating experiences that don’t connect you to life’s essential energy. You become more selective about where you spend your passion, more honest about what genuinely moves you, more willing to cross thresholds that younger, more fearful versions of yourself avoided.

The evangelical lie that older people should “outgrow” such concerns reveals how little institutional Christianity understands about human flourishing. The erotic isn’t about youth—it’s about aliveness. And aliveness becomes more precious, not less, as we age.

The Spiritual Implications

Here’s what my evangelical years couldn’t teach me: the erotic is inherently spiritual because it connects us to the creative force of existence itself. Every artist, every lover, every person who has ever been moved to tears by beauty understands this intuitively.

The institutions that taught me to fear my own aliveness weren’t protecting my soul—they were domesticating it. They wanted compliant congregants, not awakened human beings. The erotic threatens institutional control precisely because it teaches us to trust our own experience over borrowed authority.

The Call to Authenticity

Living erotically—in the fullest sense of feeling deeply about all aspects of existence—has become my spiritual practice. It means refusing to numb out, refusing to settle, refusing to live by other people’s definitions of what’s appropriate for a 67-year-old.

It means approaching life with the same intensity I once reserved for secret pleasures. It means treating conversations, meals, art, travel, even solitude as potentially erotic experiences—opportunities to feel deeply alive.

This isn’t about abandoning wisdom for recklessness. It’s about integrating all aspects of human experience instead of living in artificial fragments. It’s about honoring the body as much as the mind, desire as much as duty, pleasure as much as purpose.

From Barcelona, where ancient wisdom and modern freedom coexist, I can finally say what I couldn’t in those American pulpits: the erotic isn’t the enemy of the sacred. It’s the pathway to it.

Sensual | Curious | Communal | Free

Inconceivable that it took 67 years to understand this? Perhaps. But beautifully, authentically possible at any age.

Watch A Two-Minute Video Shout Out To You from My Barcelona Home This Morning

Leave a Reply