Estimated reading time: 4 minutes, 51 seconds.

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes, 51 seconds.

Many Christians have come to believe dehumanization of others is an acceptable—and yes, a necessary practice.

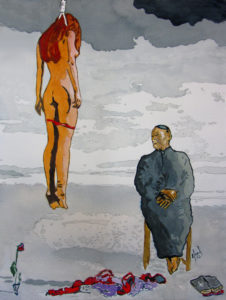

Dehumanizing others is the process by which we become accepting of violations against human nature, the human spirit, and, for many of us, violations against the central tenets of our faith. How does this happen?

Professor Michelle Maiese defines dehumanization as “the psychological process of demonizing the enemy, making them seem less than human and hence not worthy of humane treatment.”

Dehumanizing often starts with creating an enemy image. As we take sides, lose trust, and get angrier and angrier, we not only solidify an idea of our enemy, but also start to lose our ability to listen, communicate, and practice even a modicum of empathy.

Once we see people on “the other side” of a conflict as morally inferior and even dangerous, the conflict starts being framed as good versus evil. Maiese writes, “Once the parties have framed the conflict in this way, their positions become more rigid. In some cases, zero-sum thinking develops as parties come to believe that they must either secure their own victory or face defeat.

Maiese explains that most of us believe that people’s basic human rights should not be violated—that crimes like murder, rape, and torture are wrong. Successful dehumanizing, however, creates moral exclusion.

Groups targeted based on their identity—gender, ideology, skin color, ethnicity, religion, age—are depicted as “less than” or criminal or even evil. The targeted group eventually falls out of the scope of who is naturally protected by our moral code. This is moral exclusion, and dehumanization is at its core.

I know it’s hard to believe that we ourselves could ever get to a place where we would exclude people from equal moral treatment, from our basic moral values, but we’re fighting biology here. We’re hardwired to believe what we see and to attach meaning to the words we hear. We can’t pretend that every citizen who participated in or was a bystander to human atrocities was a violent psychopath.

The point is that we are all vulnerable to the slow and insidious practice of dehumanizing, therefore we are all responsible for recognizing it and stopping it.

And social media and religion are the primary platforms for our dehumanizing behavior. On Twitter and Facebook and at church we can rapidly push the people with whom we disagree into the dangerous territory of moral exclusion, with little to no accountability, and often in complete anonymity.

We must never tolerate dehumanization—the primary instrument of violence that has been used in every genocide recorded throughout history.

(Most of the words above have been excerpted from Brene Brown’s thought-provoking book Braving The Wilderness: The Quest for True Belonging and the Courage to Stand Alone. I strongly encourage you to buy and read now. Thanks so much to my new friend LeAnne Frank for recommending it to me.)

The following words are mine:

I have found Christians to be merciless dehumanizers towards their leaders and peers who have “sinned” but ready to tolerate the worst crimes as long as they are committed by leaders in the name of the proper politics. As a former Christian leader and a present victim of dehumanization, Ms. Brown’s words strike a painful and chilling chord.

Having served as a minister in two of America’s largest mega-churches and as an early adopter of social media, I did not have the luxury of anonymity when I sinned. I lived in a glass house. And on one fateful day in June 2011 thousands of Christians chose to dehumanize me. There are other words and phrases for it: unfollow, unfriend, block, ostracize, estrange, ghost, judge, shake the dust off their feet, and shame—to name only a few.

They began to say I was no longer the man they used to know. I was rendered invisible and untouchable. I was targeted as a non-human based on my sins—depicted as “less than” and evil.

My Christian friends and even my family took sides, discarded trust that had been built for a lifetime, and got angrier and angrier—they solidified me as an idea of the enemy, they lost their ability to listen, communicate, and practice even a modicum of empathy.

Not one of my nuclear family and only two of my thousands of former Christian friends stood up and said something like, “Wow, Randy screwed up twice in a row after a lifetime of integrity and leadership—I wonder if there could be something wrong with Randy? Perhaps he’s dealing with some sort of crisis. I wonder how I can help?”

But friends and neighbors listen up—I am the same Randy Elrod I have always been. I am a kind, loving, gentle yet tough, sensitive and sensual artistic man with feet of clay.

And I’m very hard to hate close up.

All of which makes me empathize with the children (now ladies) that were sexually mistreated by Roy Moore, and with the myriad ladies who have been verbally and sexually assaulted by Donald Trump. I cringe as I watch those men and their cohorts publicly dehumanize their accusers—and watch these politicians as they demonize and bully anyone who disagrees with them.

And it makes me question the faith of the people who dehumanized me—as I watch those same people stand behind and justify the sins of these leaders in the name of politics.

The powerful words of Brene Brown have inspired me to continue to speak out: “Sometimes owning our pain and bearing witness to struggle means getting angry. When we deny ourselves the right to be angry, we deny our pain. There are a lot of coded shame messages in the rhetoric of ‘Why so hostile?’ ‘Don’t get hysterical,’ ‘I’m sensing so much anger!’ and ‘Don’t take it so personally.’”

She continues, “All of these responses are normally code for your emotion or opinion is making me uncomfortable.”

I can hear my Christian friends and my family say as they read this, “C’mon, Randy, suck it up and stay quiet, or as a fine christian lady said to me yesterday, “People in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones”.

But if I did that, you would definitely know I’m not the same Randy Elrod you’ve always known—and used to love.

Leave a Reply